Before I took up my PhD studentship, I was (fairly desperately) job-hunting for a new curatorial role. I’d finished my MA in Curating in January 2016 to a job offer of a maternity cover position as Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at a national museum, feeling fairly smug that I’d now “made it” and was on my dream career ladder heading towards curatorial success. Early into 2017 I came crashing down to the reality that gallery/museum work is extremely insecure and hard to break into, even with experience, qualifications and enthusiasm. My line manager at my previous role had told me that he hoped to be able to make me a permanent staff member but this came at a time of mass voluntary redundancy and funding cuts and was therefore not approved by Senior Management. My studentship interview thus came after months of temping, lengthy job applications and eight unsuccessful interviews for curatorial roles, the feedback of each (apart from one disaster one which I may go into in some future blog post) was “we really liked you, but someone else had better experience.” At this point I’d been so broken down by the process that I couldn’t quite believe it when my now supervisor rang me 10 minutes after the interview to enthusiastically offer me the position.

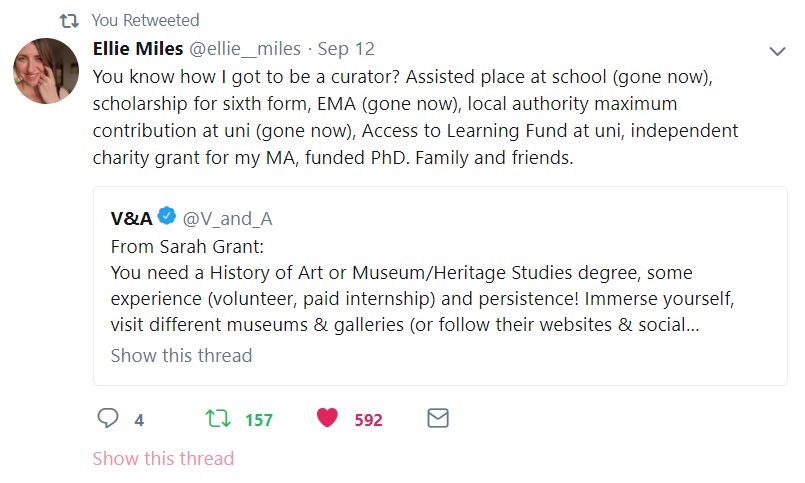

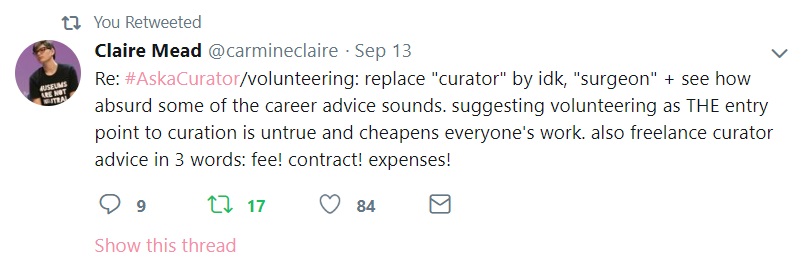

I, like many others, was therefore a little enraged by the recent “#AskACurator” discussion on twitter which highlighted volunteering and unpaid internships, as well as what can be very costly postgraduate courses, as the only way in to the increasingly competitive sector.

Something really needs to change if this is true as it closes the door to many who simply cannot afford to work for free and/or fund further education. I had to move back in with my parents for six months during my job hunt, which is also just not a possibility for many people. I’m fortunate to now have funding for a three year PhD programme, which I’m hoping will further enhance my employ-ability and help me make more contacts, but again this is not a possibility for everyone. Such elitism and lack of funding opportunities or salaried work experience leads to a further lack of diversity within arts institutions which, lets face it, are already predominantly institutions run by (and often for) the white middle class.

Ellie Miles, a curator I came across through following this hashtag on Twitter, has written a good blog post on her experiences of this with some tips and resources here.